The Epic of Gilgamesh

The cuneiform writing system of the ancient Middle Eastern nations first began to be deciphered in the 18th and early 19th centuries. Sir Henry Rawlinson (1810-95) from Oxfordshire was one of the pioneers of this, and he spotted an engraving in three languages, one of which, Old Persian, had already been adequately translated, and from that he was able to decipher the Babylonian and Assyrian versions by 1850.

Meanwhile, Sir Austen Layard (1817-94) discovered the buried cities of Nimrud and Nineveh in Iraq and sent thousands of clay tablets back to the British Museum in 1850 and 1853, which prompted thousands more to be sold to them until they had a collection of some 85,000. They were inscribed with the languages Rawlinson had found.

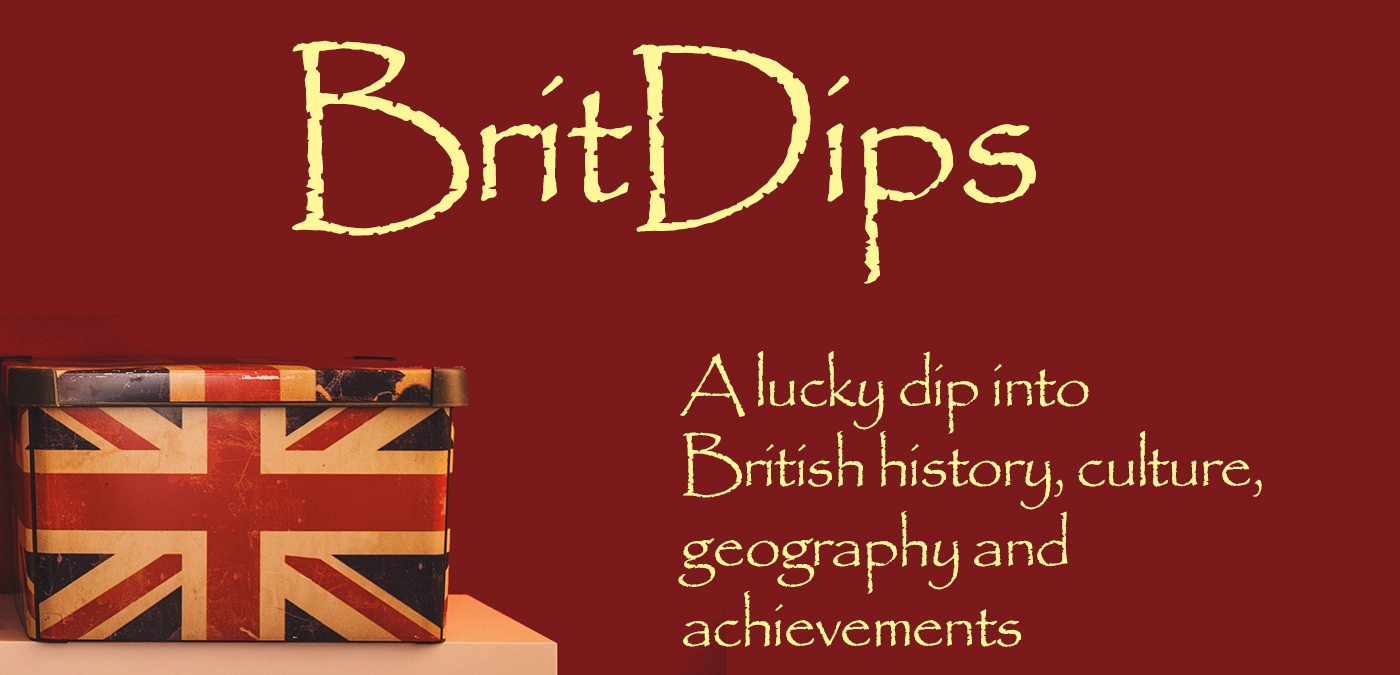

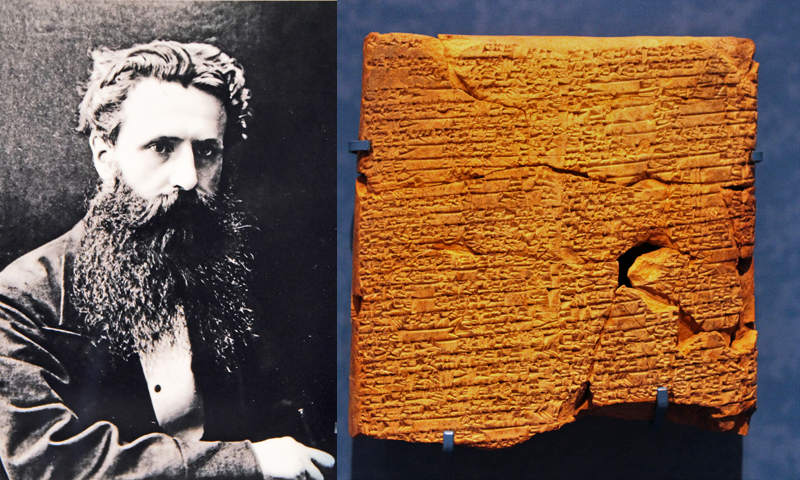

George Smith (1840-76) grew up near the Museum and was fascinated by the inscriptions and explanatory publications of Rawlinson and Layard. In 1866 he was employed as the Museum’s first salaried Assyriologist and by 1872 had made astounding progress. He had discovered the oldest existing literary work, ‘The Epic of Gilgamesh‘, judged to be more than 4,000 years old. It recounts the king’s exploits and, Smith joyously saw, the same Flood story as described in Genesis. Smith died of dysentery on a subsequent journey to Nineveh.

(Images LtoR: George Smith by Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin, one of the 12 Epic tablets by Zunkir – both at Wikimedia Commons, both CC BY-SA 4.0)