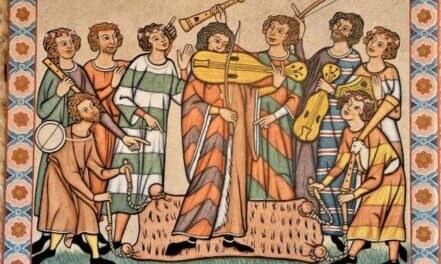

Middle English

In the period immediately following the Norman Conquest of 1066, there were three main languages spoken in England ~ Old English (O.E.), Latin and French ~ and each served a particular function and part of society. After some inevitable intermingling, Middle English (M.E.) emerged as the new, enriched, multi-purpose tongue. Its French elements enabled the expression of fresh ideas, though it retained its O.E. base.

M.E. blossomed from approximately 1100 to 1450 and it doubled the lexicon from 50,000 to 100,000 words, an astonishing leap. It changed English grammar, pronunciation and spelling, the latter helped along by Caxton’s introduction of the printing press. Whereas O.E. relied on numerous word endings to convey meaning, M.E. did away with most of those and used prepositions and word order instead.

Many of our prefixes and suffixes originate from M.E., as do the auxiliary verbs ~ be, do, have. Consonant sounds began to have soft and hard versions and vowels changed too. The influx of French architects, artisans, musicians and other pre-Renaissance practitioners brought numerous words and phrases that appealed to English ears and were absorbed into the language, especially if there were no existing equivalent. By the end of the M.E. era, English was set fair for a burgeoning literary output.

(Top image: Hans at pixabay.com)